By Common Ruin

Originally appeared in Heatwave Magazine #1, Summer 2025

Refuge

A thicket of spindly trees spread out in every direction, crisscrossed by gravel roads gouged into steep hillsides. Late afternoon sun struggled through the closed canopy, weakly reaching between the monotonous trunks of plantation timbers. Our worn-out boots crunched over a carpet of dead twigs as we wound our way up a faint trail roughly parallel to a deeply incised stream.

It was 2010 and the Great Recession was well underway. I was staying on an old farmstead in the Cascade foothills east of Kalama, Washington — a dreary mill town on the I-5 highway. I was picking up odd jobs and interning at a permaculture project in exchange for a design certification, which could potentially help me to land some work back in the city. The area still held natural beauty, especially along the river, but the hills had been mutilated. Woodlands which Indigenous peoples had tended for millennia were laid to waste by the timber industry, then replanted as “working forests” with just a handful of species. These were doomed to be grown and re-cut in an interminable cycle, with diminishing returns traceable in the erosion of the hills themselves, and the decay of the towns the industry had once built.

I was hiking with D, my internship boss. He grew up on the farm where I was staying, raising pigs and living with his folks in a house which had since burned down. When I met him, he was living in the old pig barn which he had converted into a cabin. He had been in the military and then earned a masters in environmental engineering, but his income of late came from installing gardens for yuppies down in Portland, work rendered scarce by the recession. So he tried teaching, launching an ill-fated permaculture education project. I’d soon learn that he was virtually broke, the whole project was about to implode. Like the remains of the burned house strewn with melted aluminum siding and flakes of lead paint, our society seemed generally unable to function or decompose.

“Check this out!” D called from up ahead. The ground had begun to level out, and a break appeared in the trees, which I might have guessed meant another clear cut. Instead, I noticed a rising chorus of birds and frogs as I approached. And then I gazed out upon what felt like another world. Before us lay a golden chain of ponds, their surfaces illuminated by the afternoon sun, reflecting the dance of swallows in the air above. They rose like terraces up the slope, separated by small dams and waterfalls, bordered by wildflower-studded banks. The dams were alive, sending up shoots of willow and red osier dogwood which bore buds and bright new leaves. Skillful efforts had transformed this stretch of watershed. The dams slowed the water of the creek, spreading it over a broad area. The saturated soils offered wetland plants and deciduous trees — elsewhere confined to narrow ravines — a broader foothold, laying the foundations for this thriving scene.

Decaying towns, devastated forests, the ruined farm on which I lived and the infrastructure joining them — all were residues of the capitalist relations which structure our society and constitute our species. But at that beaver complex, I saw a glimmer of life beyond capitalist logic and a cloistered humanity.

Ecosystem Engineers

A tool-using mammal with a seemingly innate drive to radically alter their environment: this description could just as easily apply to beavers as to humans. These creatures alter landscapes on a fundamental level by constructing extensive complexes of dams and canals. It’s no exaggeration to say that beavers have transformed habitats on a continental scale. North America’s beavers once “submerged 234,000 square miles … [resulting in] a watery country, a matrix of ponds and swamps, marshes and wetlands, damp mountain meadows and tangled bottomlands.”1 Far from leaving ecological devastation in their wake, beavers create “a profusion of life-supporting habitats that benefit nearly everything that crawls, walks, flies, and swims.”2 Beavers have been enhancing habitats for perhaps 24 million years, contributing to the profusion and evolution of a myriad of other species.3

If you read anything about beavers, you are bound to encounter descriptions of them as ecosystem engineers. This term helps emphasize that ecosystems are dynamic compositions of interwoven processes. But designating only a handful of animals as “ecosystem engineers” risks obscuring the fact that all life processes contribute to the co-production of ecosystems. However, beavers, like humans, are among the few species “that can significantly change the geomorphology, and consequently the hydrological characteristics and biotic properties of the landscape.”4 So ecosystem engineer remains a useful descriptor for this sort of fundamental alteration to conditions, under the broader concept of niche construction. Whereas earlier evolutionary theory posited unidirectional causal relationships between organisms and environments — in which organisms adapt to fit preexisting niches — niche construction recognizes reciprocal causality5 wherein “organisms themselves shape or “construct… the external conditions of their existence” as well as “their experience of those external conditions.”6

Ben Goldfarb, author of Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, has referred to beavers as humanity’s “closest ecological and technological kin.” Humans have long recognized the ecological significance of beavers and similarities between these creatures’ activities and our own niche-constructive or socioecological practices. Perhaps the oldest of Blackfeet medicine stories center on the supernatural beaver, Kitaiksísskstaki, transferring knowledge to human beings, including “the power of the waters.” These gifts also signified a compact, a relationship with mutual obligations.7 Colonization and the ongoing entrenchment of capitalism, however, have transformed human socioecological relations and subjectivity, influencing the activities we engage in, the environments we inhabit, and the language and concepts we use to make sense of our world. Examining the history of human interactions with beavers illuminates the role of capital in shaping our reality, the paths which led here, and perhaps some paths leading elsewhere. In agreement with Endnotes’ view that “Communist theory is an apparatus for thinking the experience of life dominated by capital and the movement beyond it,”8 this essay dialogues with texts like Goldfarb’s Eager, but from a communist perspective.

Beavers as Kin

Long before colonization and the development of ecology as a science, Indigenous societies of North America recognized the ecological significance of beavers and parallels between beavers’ world-shaping activities and their own stewardship practices. While it is impossible to adequately summarize the range of Indigenous views and practices, this recognition has generally involved enacting reciprocal relationships between people and beavers, a tendency to regard beavers themselves as persons or kin, and an incredible variety of stories involving beavers. Through these actions and stories, people are situated within and find agency through relational webs as bearers of gifts, knowledge, and obligations. Kinship as a concept emphasizes this sort of connection and relationality.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson writes of Nishnaabeg cautionary tales against excessive hunting and exploiting others’ labor.9 Rosalyn LaPier relays Blackfeet understanding of the crucial role that beavers played in bringing water to arid territories, which inspired the people to prohibit beaver hunting. This too was reinforced through story. LaPier emphasizes that this was not a simple or naive environmental moralism; Blackfeet traditionally understood their own power and agency as flowing through relationships with other kinds of beings, and they stewarded the land in accordance with these principles.10 Indigenous niche-constructive socioecological practices such as those touched on here — and the subjectivities which shape and are shaped by them — saw to it that beaver populations of sixty to four hundred million were co-creating a world of abundance alongside human beings, until the advent of the fur trade.

Beavers as Commodities

The fur trade was the first tendril of the emerging capitalist world system to probe and strangle its way across much of the North American continent. Beginning in the earlyseventeenth century, beaver pelts became “North America’s most coveted commodity” and they would continue to be sought after for over two hundred years.11 The trade lay at the heart of many struggles and alliances, fueling the conflict between settlers, Indigenous powers, and the British Empire which ultimately spawned the United States.

Fifteenth century furriers devised a means of producing unparalleled felt from beavers’ fine undercoats, and the upper classes of Europe were stricken with an insatiable lust for hats and other items made from this material. Upon learning of North America’s abundance of beavers — and having already destroyed most of their continent’s fur-bearing wildlife — Dutch, Swedish, French, and British merchant capitalists raced to secure supplies of beaver furs for their respective empires.

As part of a “maelstrom of colonialism,”12 the fur trade radiated violence outward through the same processes that concentrated its fortunes in European capitals and colonial outposts. Whether introducing socially destabilizing commodities like guns and alcohol, or mundane items like textiles and kettles, fur traders were frequently the first Europeans to enter Indigenous territories, serving as vectors for devastating epidemics. The trade shaped political conditions to which Indigenous societies had to respond. Against a backdrop of plagues and uncertainty, control of fur-rich territories and trade routes meant secure access to firearms and trade goods, along with more advantageous alliances. In other words, it could be key to a group’s survival. Preexisting tensions within and between Indigenous groups flared into open hostilities, and a range of new tensions were introduced.

Precolonial hunting and trapping had been conducted in accord with practices of reciprocity. Social activity had never before revolved around the mass procurement of beaver pelts, let alone procurement for exchange. Now, in many regions Indigenous groups began relating to pelts as commodities just as their trade partners did, carrying out much of the trapping and processing according to this new logic. Beaver pelts came to be treated as a sort of currency, at times euphemistically referred to as “hairy bank notes.”13 The Hudson’s Bay Company produced “Made Beaver” coins representing not quantities of precious metals but whole or fractional quantities of quality beaver pelt. The result of this commodification was that the creatures who had nurtured the ecosystems of a continent were killed by the tens of millions.

So long as their territories and ecosystems were intact, Indigenous groups maintained significant leverage in trade relations, with, for example, Algonquian and Haudenosaunee peoples often setting the terms for European traders.14 But the British increasingly saw the maintenance of relatively amicable relations with Indigenous producers as an impediment to profit maximization. After the Seven Years War (1756–1763), backwoods settlers and the colonial bourgeoisie escalated their expropriation of Indigenous territories. Other than direct violence, racialization, the claiming of the best farmland, the over-hunting of game, and the banning of ecological practices like controlled burning were all ways that settler society displaced Indigenous peoples and pressured survivors towards market dependency.15 In 1808, Thomas Jefferson wrote to Merriweather Lewis that “Commerce is the great engine by which we are to coerce them, and not war.”16 Nevertheless, the US military and civilians spent over a century waging war against Indigenous peoples and their socioecological practices, which threatened the capitalist order.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the fur trade had wiped out commercially viable beaver populations across much of North America, and European fashions shifted towards Chinese silk. The trade had incentivized a rapid explosion of exploration and expropriation before slowly imploding. Trappers had blazed trails that settlers followed. Profits amassed through the fur trade were reinvested in its wake, serving as startup capital for agricultural, timber, and mining enterprises. The wage laborers set to toil in these industries would not be harvesting wildlife from landscapes left relatively intact but would instead be transforming the land itself. This shift to more capital-intensive forms of productive activity would foster a new attitude towards the animals whose bodies had once been fuel for the engines of empire.

Beavers as Impediments

In North America, the plunder of ecosystems set capital in motion. “Formal subsumption” refers to situations where capital takes hold of a labor process but leaves it unchanged. This is never enough, as imperatives for ever-increasing productivity run up against natural and social limits. So, capitalists deploy new technologies and social practices aimed at maximizing control and increasing the relative surplus value it can extract from labor, reshaping production, social life, and the physical world. This more fundamental tranformation is called “real subsumption.” Nonhuman nature presents just the sort of unruliness that real subsumption strives to discipline and transform.17 Since the concept of niche construction includes organisms’ social practices along with material reconfigurations of environments,18 we may consider the real subsumption of nature to be a sort of capitalist niche construction. Our capacity to reconfigure the environment has been hijacked by capital and turned against us, confronting us as an alien power.

Beaver ecosystem engineering eventually presented barriers to the expansion of capitalist production. Dams downstream from agribusinesses risked causing floods that would damage fields and pastures. Dams upstream of water-wheel-powered factories threatened the flow which animated the machinery. No longer lucrative, beavers were becoming the opposite: impediments to accumulation. They would still be trapped or shot on sight, but now simply because they were in the way.

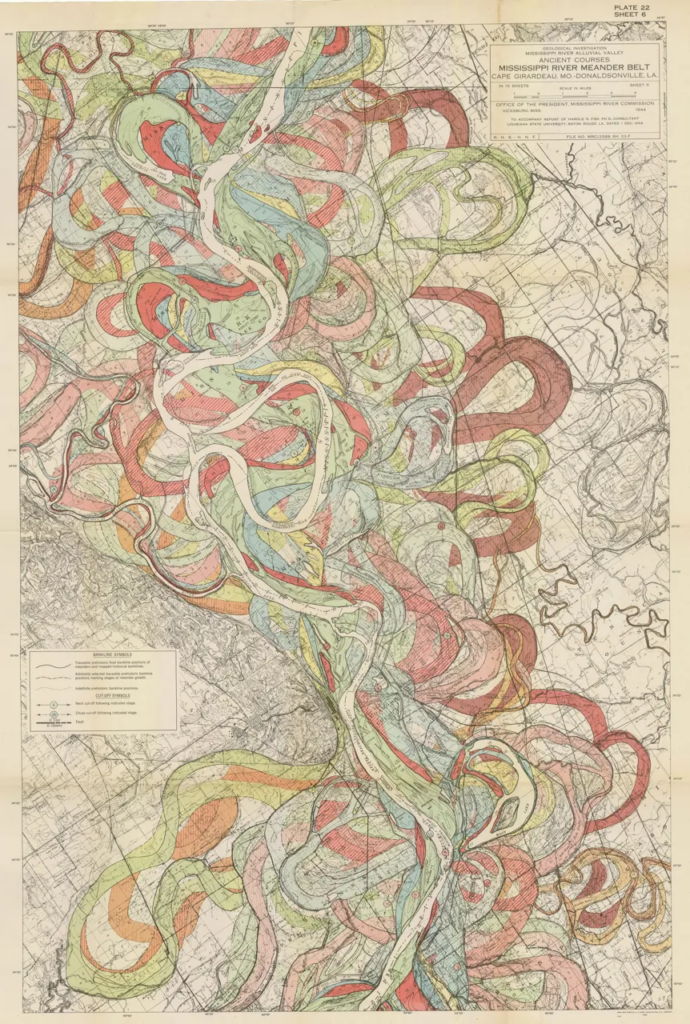

Rivers themselves were reconceived as mechanisms for circulating commodities, irrigating plantations, and supplying power to industries. The continent’s wild rivers were still vast and maze-like expanses of beaver dams and log jams, characterized by patchiness and discontinuity,19 as well as unruly rapids and currents. In 1874, a US congressional committee declared that post-Civil War America could be reunited by waging a new kind of war — a war against the Mississippi river.20 The US Army Corps of Engineers was set to the task. The war on rivers would spread across the continent and continues today. The Army Corps, “fixated on turning rivers into freeways for shipping, embarked upon an anti-logjam crusade. … Beaver dams, in many cases the most visible blockages, were not spared.”21

Capital strives to increase the rate of exploitation of labor — in large part by mechanizing and automating production processes — leading to an insatiable appetite for fuel, and incentivizing the further subsumption of nature. Beginning during the Great Depression, the Army Corps set about constructing a series of enormous hydroelectric dams, intended to revive the economy with an abundance of cheap electricity. The real subsumption of rivers like the Columbia undermined Indigenous social autonomy and inter-species kinship relations along the West Coast. Celilo Falls was the most significant Indigenous fishing site along the Columbia River, and has been called the oldest continually inhabited location on the continent, dating back 15,000 years. But in 1957 it was submerged by the Army Corps, sacrificed to bring The Dalles hydroelectric dam online.22 The subsumption of nature entails the eradication of alternative niche-constructive social practices.

Between the seventeenth and early twentieth centuries, North American beavers were nearly driven to extinction. In terms of ecological impact, geomorphologist Ellen Wohl has called it the “great drying,” and Leila Philip notes that, “more than 80 percent of the riverside marshes, swamps, lakes, ponds, and floodplain forests of North America and Europe have disappeared.”23 Beaver populations have risen in recent decades but remain a fraction of precolonial levels. The destructive reconfiguration of life on Earth is commensurate with the accumulation of capital. The scale of harm wrought is difficult to fathom. The problem is what Daniel Pauly calls “shifting baseline syndrome.”24 As capital’s treadmill is wrought upon the planet, each successive generation is prone to assuming that the conditions into which we are born are normal or even natural. We notice destruction wrought during our lifetimes but are far less likely to comprehend the full severity of the situation. What we take as a baseline is already a ruin. By destroying or subsuming all ecological and social impediments, capital constructed a world with value as its center. The center cannot hold and that world is falling apart.

Beavers as Saviors… of Capital?

If you wanted to incinerate California, one place to start would be to kill as many beavers as possible. Without them, millions of acres of wetlands and moist riparian zones would shrivel down to spindly ribbons, no longer recharging groundwater, serving as natural fire breaks, or providing a verdant refuge for wildlife during a fire. Next, you could forcibly shut down Indigenous ecosystem engineering practices, especially the controlled use of fire, turning what were once carefully nurtured open forests and savannas into tinderboxes. Then you could shunt the rivers from watersheds into “a pipeshed”25 directed into suburban lawns, concentrated animal feedlots, and above all, into mercilessly over-tilled, water-hungry croplands of the Central Valley, effectively evaporating as much moisture back into the atmosphere as possible. To maximize harm, you’re going to want to destroy at least 90 percent of precolonial wetlands. Finally, you would want to pump enough carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that it alters precipitation patterns, provoking unprecedented droughts and raising summer temperatures to record-shattering highs. After that, any spark would do. If you wanted to incinerate California, you wouldn’t have to do a thing. Capital has done it all for you. Altadena and Pacific Palisades burned during the time it took to complete this essay.

Elsewhere, floods rip through valleys with unprecedented frequency and ferocity. Carbon emissions have yielded an atmosphere on steroids, pumping out intense storms carrying significantly more water vapor with each degree of warming. It may seem paradoxical, but beaver wetlands mitigate the effects of flooding. By slowing and spreading out water, beaver wetlands and meadows facilitate storage and infiltration, while reducing the sediment load of downstream runoff. From Asheville, North Carolina to Valencia, Spain, climate change highlights the absence of these creatures and their work.

As the world falls apart around us, capital scrambles to ensure further accumulation. Under these conditions, yet another shift is taking place in relations and attitudes towards beavers. For decades, there has been a push to frame ecology in terms of economics. Monetary values are assigned to the processes of life in terms of services provided to the economy, tasks which would otherwise be resource and labor intensive. In this light, beavers have been rechristened as service providers.26The dynamic wetlands they would create are circumscribed, with a few animals introduced here, a few killed there, whatever it takes to stabilize infrastructure. Working beaver wetlands are used as sewage treatment ponds, or to soak up polluted highway runoff. For flood and storm-water management, “the cost-benefit ratio of using beavers is astronomical” according to a Maryland engineering firm.27 In drought-stricken western states, agribusinesses utilize beavers to boost productivity. “Beavers increase production tenfold” and they “do it for free,” said the manager of a three-million-acre Nevada cattle ranch.28 In other words, beavers are to assist in capitalist niche construction, extending the pseudo-life of this grim machine for a bit longer. And the longer that is, the more dire the future prospects for everyone else.

Processes of Communist Life

Salvaging the ecological preconditions for lives worth living entails breaking from the social logic that dominates and reroutes proletarian niche-constructive capacities towards capitalist accumulation and the common ruin of Earthly life. However, some implications of breaking from this logic remain under-theorized. Marx and Engels noted the tendency wherein people mistake concepts derived from particular historical social relations for immutable facts.29 We proceed in error if we fail to consider that communist subjectivities, needs, and desires will diverge from our own. I’ve sought to illustrate how the imperatives and deepening entrenchment of capitalism have shaped relations and attitudes towards beavers. More broadly, the abstract domination which characterizes capitalist social relations — whereby access to the means of life is mediated by value — fosters a sense of ontological separation between humans and our living world. This separation is neither transhistorical (as inter-species kinship practices demonstrate), nor is it validated by science.

Contemporary works in biology, ecology, and the philosophy of science abound with descriptors of life such as mosaic, processual, and entangled. The development of each organism is profoundly modulated by the environment, which, in turn, is shaped and constituted by the bodies and activities of other organisms.30 Microbes co-create human bodies, endosymbionts power our cells, and eight percent of our genome is of viral origin and responsible for essential processes.31 Your ability to read this, and “every thought that has ever passed through your brain was made possible by plants.”32 We are “fluid processes; metabolic streams of matter and energy,” unable to “function, or even persist, independently of the entangled web of interrelations” linking us with other beings.33

Cloistered notions of self and species are “directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse” of capitalist social relations.34 “Capitalism is founded upon the insertion of the logic of valorisation into the gap between life and its conditions,”35 engendering an ontological sense of separation between our species and the rest of the biosphere. Further, because the creation of surplus value — the secret of profit making — is only achievable through the application of living human labor in the production process, “nonhuman inputs that cannot be objectified in the form of value… become merely vessels for the objectification of human labor.”36

Endnotes describes communist revolution as “an accumulation of ruptures,” wherein rupture denotes a qualitative break with the existing social order, beyond mere disruption, that “calls life itself into question, but in a way that allows us to carry on living.”37 But the means of carrying on living seem further from reach with each passing year. If there is to be revolution, it will be here, in a world scoured by fire and flood, hollowed out by mass extinction and the decline of biodiversity. It will unfold into a near-future defined by unprecedented migration, climate breakdown, and perhaps the fallout and complications of so-called geoengineering. Any communist theory worthy of consideration must be situated on this terrain.

Thinking revolution as the enactment of niche-constructive communist measures — relations and practices unfettered by the law of value, in opposition to all forms of domination and exploitation, grounded in the entangled reality of Earthly life — is both a foundation upon which to struggle against capital, and a proposal for salvaging as much as possible from the mangled web of life. The abolition of value is not a return to an original ontological unity — there is no such thing. But as rupture extends and deepens via communist niche construction, the activities through which we craft our lives, including how we use technology, will shape new subjectivities. This would be a communism of the web of life, not the human species, a dynamic mosaic of relations as varied as the terrain of the earth, without a center. The real movement stirs in our time beneath banners bearing messages like “Mní Wičóni” (Water is life) and “Nous ne défendons pas la nature, nous sommes la nature qui se défend” (We don’t defend nature, we are nature defending itself).

If, as Roland Simon once argued, the “abolition of value is a concrete transformation of the landscape in which we live,”38 then we might once more look to beavers, those great transformers of the landscape, for some principles to guide niche construction. Echoing Endnotes, we might say beavers rupture the flow of rivers. Through an accumulation of ruptures, they construct niches that are not only suitable for more beavers (and therefore the proliferation of further rupture), but for innumerable other species. This includes, of course, the plants on which beavers depend, their means to life. The wetland and the beaver exist symbiotically: the wetland is an extension of the beaver’s life into the landscape, melded with the lives of other beings. This continual process recursively builds upon itself. To speak more abstractly, we see the conditions wherein new forms of life are made possible and an expansive sense of self is made realizable by undertaking measures “which fold themselves into each other and which ultimately succeed in giving to the overall organisation of the world an altogether different quality.”39 By acting together with the knowledge that our lives are quite literally constituted through socioecological processes, communist wealth will present itself not as an immense accumulation of commodities but of relationships, whereby the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.

Reciprocity

A few weeks ago, I wandered down the train tracks, hopped a fence and waded across a river to a beaver complex on the fringe of the city where I live now. As I looked upon a crescent-shaped dam, its form arcing into the current, dissipating the river’s force outward, I recalled those ponds that D showed me. It had been years since I thought of that place, but now I was wondering, hoping that it still existed. At home, I pulled up a recent satellite image. I wish I could tell you that it’s still there. Maybe I looked in the wrong place, but I saw no sign of it, just clear cuts, plantations, and a maze of logging roads gouged into the Earth. Beavers are struggling against capital, struggling to remake the world, and would gift their knowledge to those of us who would accept it. I have learned from them, and here I have passed a bit of that knowledge on to you. But their gift is not without obligation. How might we reciprocate?

1 Ben Goldfarb, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter (Chelsea Green Pub, 2018), 36.

2 Goldfarb, Eager, 8.

3 Frances Backhouse, Once They Were Hats: In Search of the Mighty Beaver (ECW Press, 2015), Chap. 2.

4 Frank Rosell, et al., “Ecological Impact of Beavers Castor Fiber and Castor Canadensis and Their Ability to Modify Ecosystems,” Mammal Review 35, no. 3–4 (2005): 248–76.

5 Joseph Rouse, Social Practices as Biological Niche Construction (University of Chicago Press, 2023), Chap. 2.

6 Sonia Sultan, Organism and Environment: Ecological Development, Niche Construction, and Adaptation (Oxford University Press, 2015), Chap. 2.3.2.

7 Rosalyn R. LaPier, Invisible Reality: Storytellers, Storytakers, and the Supernatural World of the Blackfeet (University of Nebraska Press, 2019), Chap. 4.

8 “We Unhappy Few,” Endnotes 5 (2019).

9 Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance (Univ of Minnesota Press, 2020), Chap. 5.

10 LaPier, Invisible Reality, Chap. 4.

11 Pekka Hämäläinen, Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America (Liveright, 2023), Chap. 6.

12 Ned Blackhawk, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Harvard University Press, 2008), Chap. 2.

13 Eric Jay Dolin, Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America (W. W. Norton & Company, 2010).

14 Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (Cambridge University Press, 2010), Chap 2.

15 White, The Middle Ground, Chap 11. Note that the difference between pre-capitalist commercial activities (such as market exchange) and a society’s integration into the capitalist mode of production is defined by that society’s dependence on participation in those activities — no longer as a supplement but now as necessary for survival. For a detailed study of how this process played out on one island in the late 20th century, see Tania Li, Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier (Duke University Press, 2014).

16 “From Thomas Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis, 21 August 1808,” Founders Online, National Archives.

17 Søren Mau, Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital (Verso, 2023), Chap. 11.

18 Rouse, Social Practices as Biological Niche Construction, Chap. 2.

19 Denise Burchsted, Melinda Daniels, and Ellen E. Wohl, “Introduction to the Special Issue on Discontinuity of Fluvial Systems,” Geomorphology 205 (2014): 1–4.

20 Boyce Upholt, The Great River: The Making and Unmaking of the Mississippi (W. W. Norton & Company, 2024), Chap. 7.

21 Goldfarb, Eager, Chap. 5.

22 Shasta Kearns Moore, “Group Seeks to Recover Celilo Falls,” Portland Tribune, May 15, 2014.

23 Leila Philip, Beaverland: How One Weird Rodent Made America (Twelve, 2022), Chap. 9.

24 Daniel Pauly, “Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries,” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10, no. 10 (1995).

25 Brock Dolman, quoted in Goldfarb, Eager, Chap 6.

26 Ecologists and activists sincerely committed to beaver restoration constantly run up against limits imposed by capital. Efforts such as these can only find their full expression in a non-capitalist world.

27 Philip, Beaverland, Chap. 13.

28 Goldfarb, Eager, Chap. 7.

29 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology (1846), Chap. 1.

30 Sultan, Organism and Environment, Chap. 2.3.2.

31 David Quammen, The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life (Simon & Schuster, 2018), Chap. 77.

32 Zoë Schlanger, The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth (Harper, 2024), Chap. 2.

33 John Dupré and Daniel J. Nicholson, “A Manifesto for a Processual Philosophy of Biology,” in Everything Flows: Towards a Processual Philosophy of Biology, ed John Dupré and Daniel J. Nicholson (Oxford University Press, 2018).

34 Marx and Engels, The German Ideology, Chap. 1.

35 Mau, Mute Compulsion, Chap. 12.

36 “Tragic Theses,” Decompositions, March 9, 2023,

37 “Spontaneity, Mediation, Rupture,” Endnotes 3(2013).

38 Roland Simon, “Self-organisation is the first act of the revolution; it then becomes an obstacle which the revolution has to overcome,” in A Théorie Communiste Reader (2021).

39 Leon de Mattis, “What is communisation?,” Sic 1 (2011).